Andrew Lynch

Taking a gap year is a rite of passage experienced by hundreds and thousands of students every year in the UK. Before moving into higher education and the pursuit of a career, it offers the chance to develop valuable life and work experience that can make all the difference to their personal and professional lives.

The reasons why students take time out from their education varies from person to person, although as our gap year statistics for the UK demonstrates, there are a number of common trends apparent within the research.

To explain further, we’ve compiled a comprehensive range of UK gap year facts to reveal what students do during their break, how they fund it, the possible impact it could have on future job prospects and more.

In 2023 it’s estimated between 183,000 to 232,000 18-24 year-olds took a gap year.

On average, 29,920 students defer their university course to take a gap year each year.

For the 2022/23 academic year, 30,970 students deferred their university course, an increase of 28% from 2012 but a decrease of 15.8% from 2021.

The average gap year travelling costs £2,681 a month, or £32,175 a year if travelling for all 12 months.

Between 101,640 and 103,712 people will have travelled on a gap year in 2022.

An estimated 153,700 gap year takers will work in Britain (83%), while 59,300 will work/volunteer abroad (16%).

1 in 5 young people rely on the ‘bank of Mum and Dad’ to fund their gap year.

It would take 640 days working minimum wage for 18-20 year-olds to earn enough to travel for 12 months on a gap year.

‘Grey gap years’ see the over 60s take extended travel periods, and there is an estimated 4.82 million older Brits planning on doing so.

The definition of a gap year is a period of between 3-24 months taken out of education – usually before or after college or university – which is used to travel, work, or plan what the next steps in the individual’s life will be.

Gap years are generally taken by people between the ages of 18-25, and while many do return to complete the next stage of their education, the time spent travelling or working can create a new perspective or opportunities that otherwise may never have been realised while studying.

However, broadly speaking, a gap year can also be taken by people who have long since left the education system. For example, an entire family can take a gap year, while someone more advanced in their career taking a sabbatical could also fall into this category, or older adults entering retirement can take a ‘grey gap year’.

This makes it difficult to create a definition of a gap year that encompasses every scenario, but for the purposes of our research we will focus purely on students who take time out of their education, this is the most common way to define a gap year.

The Department for Education and Skills (DfES) estimates anywhere between 200,000 – 250,000 young people take a gap year each year. But they might not reflect what this looks like now.

These figures, however, come from a 2012 piece of research. Accounting for the change in the population of 18-24-year-olds in the UK from 2012 to 2023 (-7.1%), the number of young people taking a gap year in the UK could be closer to 183,000-232,000 for the 2023/2024 academic year.

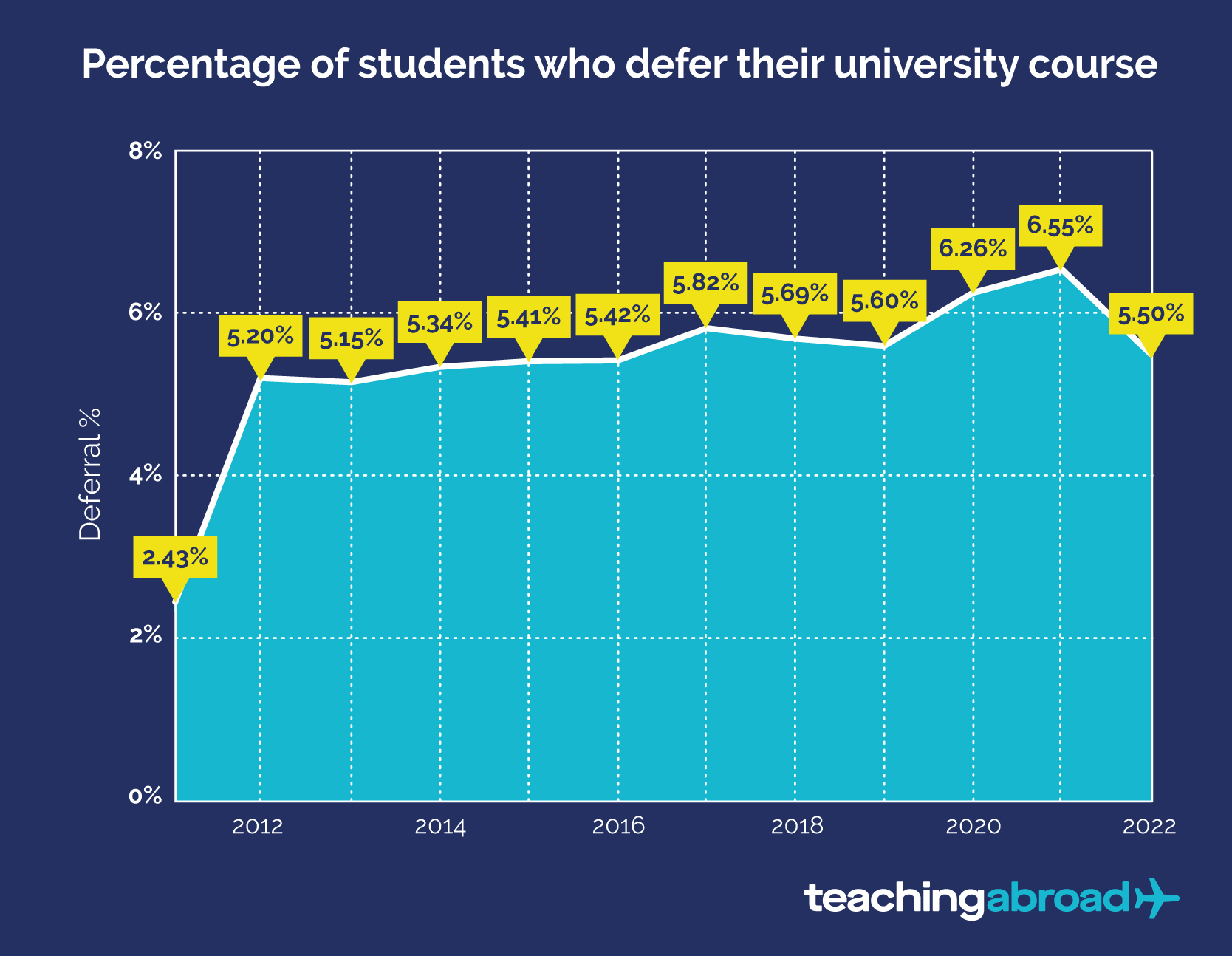

Analysing UCAS data, we can see that since 2012, there has been an average of 28,477 students who defer their course each year to take a gap year. From 2012 to the 2022/2023 academic year, the total number of students deferring their education has increased by 28% from 24,195 to 30,970.

Focusing on only the more recent years, there was a 21.32% spike in course deferrals from 2019 to 2021, rising from 30,325 students to 36,790 at the height of the pandemic. The pandemic’s impact is clear with 2020 also seeing a sharp rise, with 5,400 more deferrals than in 2019. In 2022, the number of deferrals dropped by 15.9% with 5,820 fewer than in the previous year.

When reviewing the data proportionally to the number of students applying each year, the rate of deferral has increased by 1.34%, from 5.2% in 2012 to 6.55% in 2021, which was the highest it had ever been. In 2022, the rate of deferral came back down to 5.5%

While deferrals are useful to see how many students are changing their study plans to gap year plans, this is only between 12% and 15% of the DfES’ estimation of annual gap year takers, leaving those not attending university (approx. 170,080 220,080) to make up the rest of the Government approximation.

This majority (85%-88%) will be made up of those who took gap years without applying to university at all, by applying the year after, or not taking this as their next step by going straight into work or an apprenticeship for example.

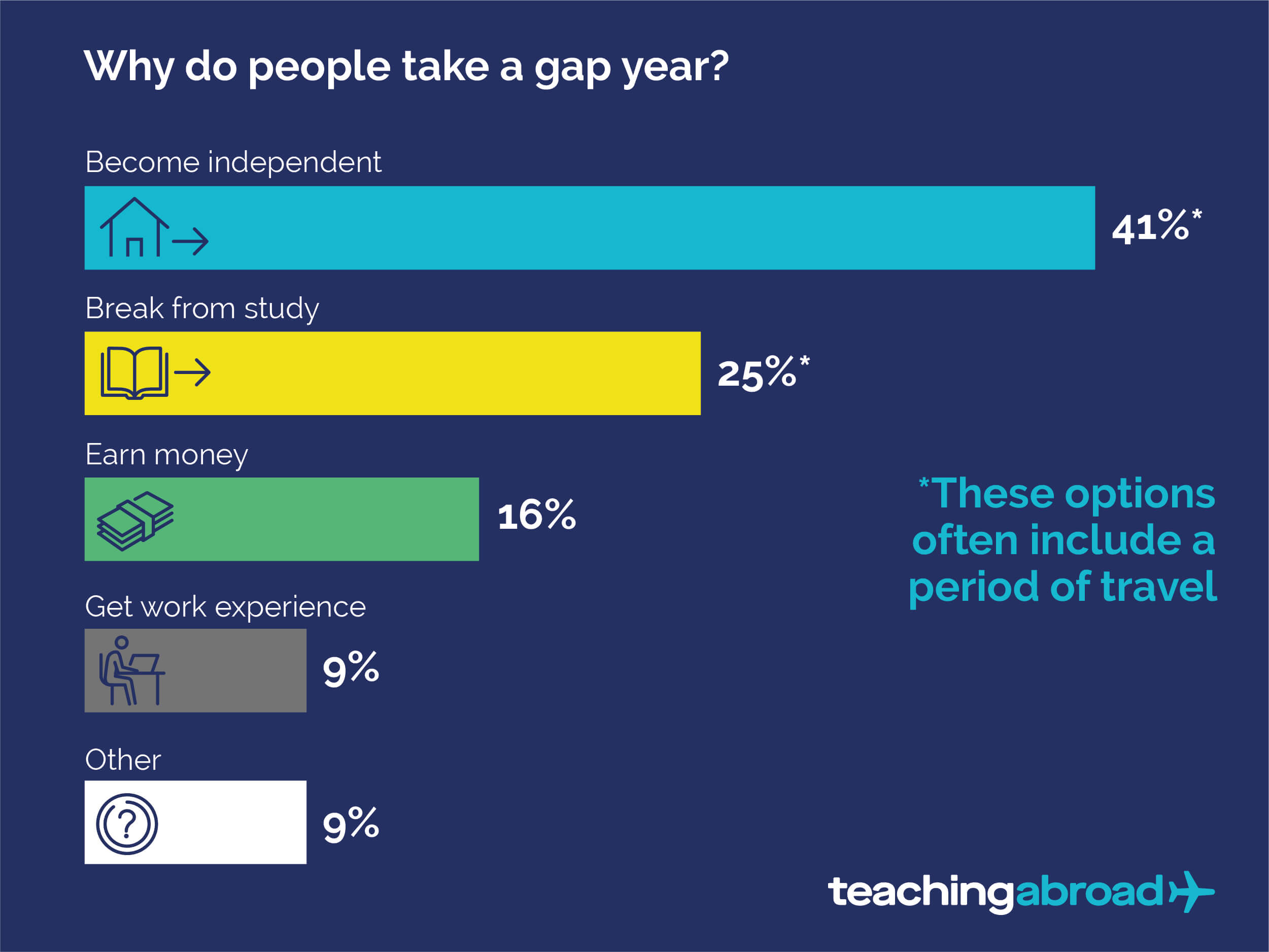

Primarily, people take gap years to do some period of travelling or to earn money through employment. Two in five (41%) students, the largest majority from Government gap year statistics say the primary reason they took their gap year was to ‘become independent’, with travel and employment being the most popular routes to achieve this goal.

After independence, simply ‘taking a break from studying’ was quoted as the second reason to take a gap year, with 28% of students doing just that. On the surface, the term ‘taking a break from study’ may sound a little vague, but this typically translates into travel, be it domestically or by venturing out into other parts of the world.

A large portion of students take gap years to focus on self-growth and developing their independence, with 40% stating this as the main reason for taking time out. This is understandable given we are talking about young people aged between 18-25 entering into higher stages of education and adulthood, a crucial time of self-development in anyone’s life.

While earning money is cited as one of the main activities of many students during a gap year, it is actually one of the lesser reasons why they take a break. Over one in six (16%) people say money is the main reason for their gap year, while only 14% decide to put their studies on hold so they can prioritise work experience and bolster their CV.

What to do on a gap year? Likely the first question many young people ask themselves when they’re unsure about their next step in life. The most common thing people do on a gap year as it turns out is work and save some money.

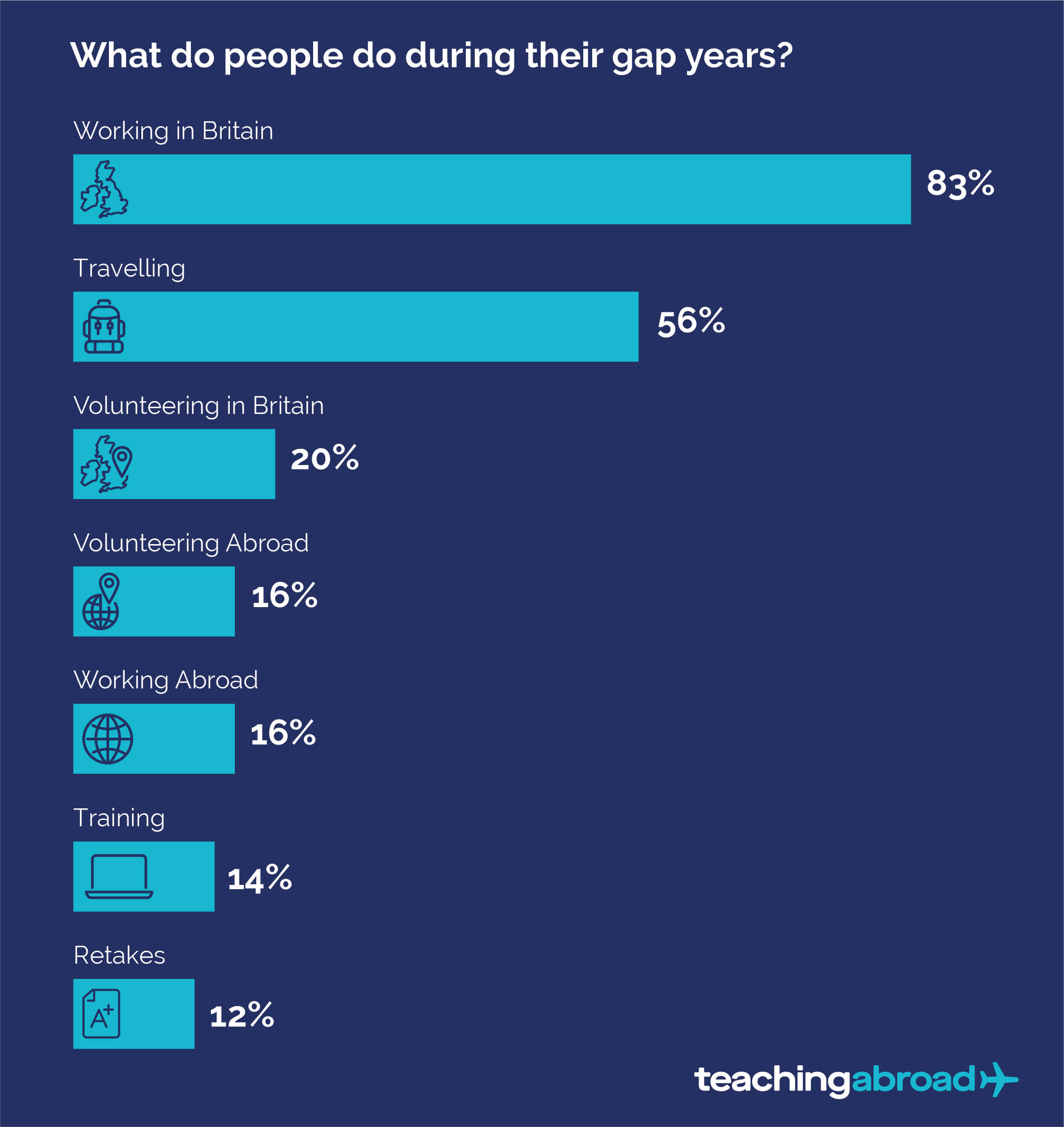

Government studies found that most young people on a gap year (83%) work in Britain, while the second largest group heads abroad for a period of travelling (56%), while one in five (20%) do some form of volunteering back home in the UK.

The full median percentages from the study can be found in the graph below:

Using 2022 gap year estimates, as well as the fact that up to 83% of people work on their gap year, estimates show that up to 153,700 people will work on their gap year.

Furthermore, by using the same calculations you can see that up to 59,300 students from the 2022/2023 academic year will have worked or volunteered abroad. We know from our own data that TEFL jobs are one of the most popular routes for teaching abroad in your gap year.

With over half (56%) travelling on their gap year, 2023/2024 academic year estimates show that between 102,480 and 129,920 people will have travelled on a gap year in 2023.

A smaller percentage are able to work in another country (16%), with similar figures for those volunteering abroad (16%).

Taking the 10 most popular countries for gap years, we can see that the average cost of a gap year is £2,681 a month ($3,263 USD), or £31,175 a year ($37,948 USD) if the person travels for all 12 months. This is almost the same amount someone earning £43,000 a year would take home (after tax) in the UK (£2,710 each month, factoring in income tax and national insurance payments only).

With travelling being a main focus for many students during their gap year, this will come at an expense for many individuals who have saved up, or for their families. Of course, the extent of their travels will dictate the cost, and the regions explored will vary this amount greatly.

Taking a gap year gives students the chance to step away from education to explore the world before refocusing on their future careers, but how do people fund a gap year?

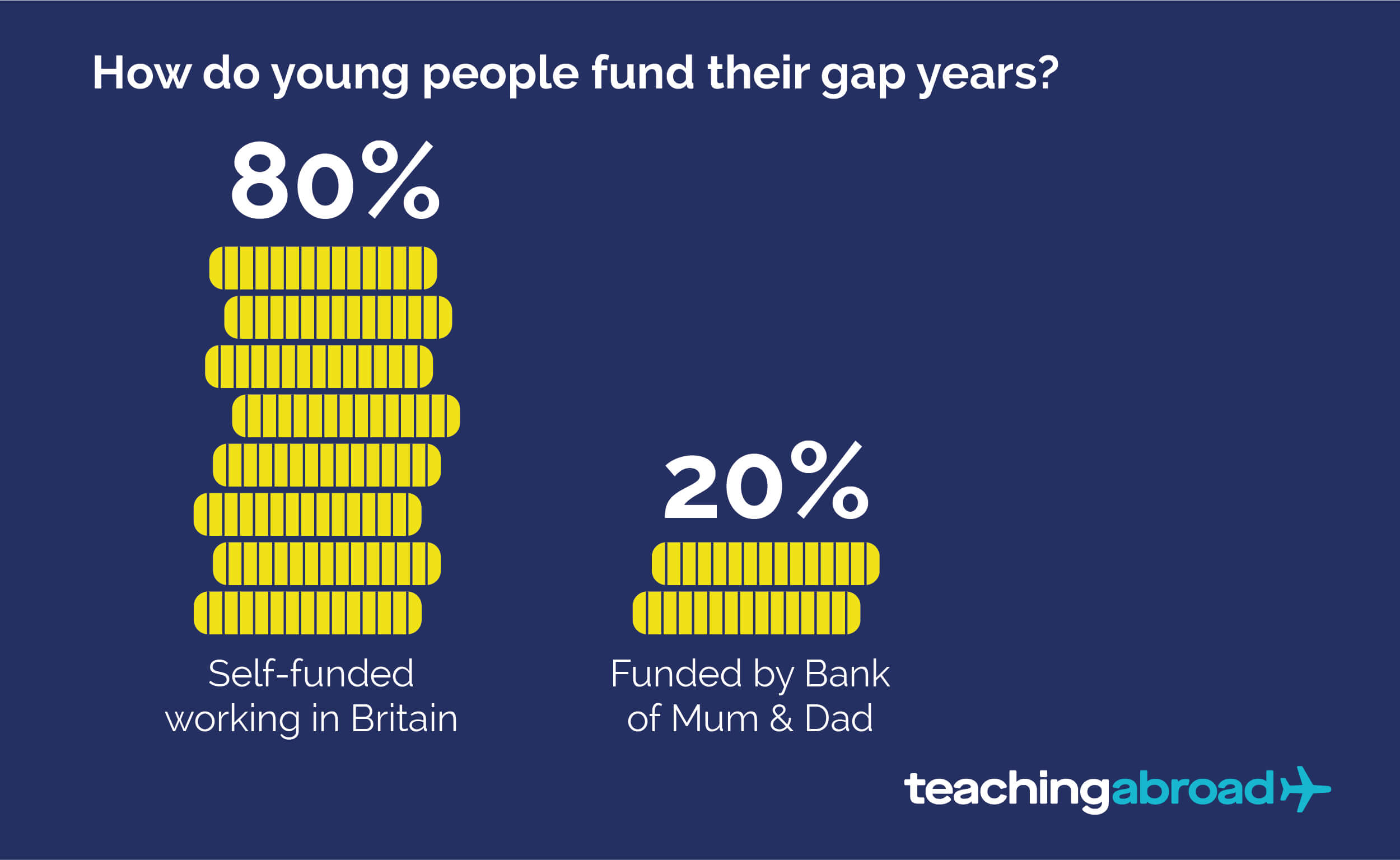

The biggest source of funding for gap years is secured by working, with four in five students taking on employment of some kind in the UK during their gap year. A smaller section of students however benefit from financial support from their parents, with 20% of gap year takers receiving money from ‘the bank of mum and dad’.

The type of work taken on during a gap year can be wide and varied, with jobs ranging from waitressing and bar work, to babysitting and working in events.

Using the minimum wage for 18-20-year-olds (£6.83), it would take around 640 days of 8-hour shifts for one person to earn enough to travel for 12 months of a gap year.

Southeast Asia is always a popular destination, with countries such as Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia appealing to students for a number of reasons, be it cost or culturally-based.

South America is also a travel hotspot for gap year takers, including the likes of Peru and Argentina, while travelling down under to Australia and New Zealand remain desired options. The USA, South Africa and India also offer varied cultural experiences for those looking to travel abroad.

In terms of expenditure, based on average monthly travel costs, the USA is by far the most expensive option, costing approximately £6,864 for a single person each month. Australia and New Zealand also require sizable travel budgets, with a monthly average of £3,705 and £3,276 respectively.

| Country | Average monthly travel costs |

|---|---|

| USA | £6,864 |

| Australia | £3,705 |

| New Zealand | £3,276 |

| Thailand | £2,767 |

| South Africa | £2,106 |

| Vietnam | £1,497 |

| Cambodia | £1,497 |

| Peru | £1,464 |

| India | £955 |

| Aregntina | £621* |

*The Argentine Peso has been unstable in recent years, so travel cost estimates for this country may be unreliable.

It’s easy to understand why some areas of Southeast Asia and South America are popular, as they sit at the lower end of the cost scale, although prices in the region have increased substantially in recent years. Despite that, India generally tends to be the cheapest, with a monthly average cost of £854.

Whether it’s to gain more independence through travel, or to seek out paid or voluntary work experience, students taking a gap year hope their time away from education will benefit their long-term goals.

A lot of importance is placed on achieving a degree at university due to the fact as many as 74% of all graduates are likely to find full-time employment. This corresponds to the 80% of people in the UK who think spending some time out of the education system adds to their employability.

Other key findings to consider include:

In the UK, 60% of those taking a gap year believe it helped them decide what subject to study at university and;

66% took their studies more seriously upon their return

In the US, 97% of students enjoyed increased maturity due to taking a gap year and;

96% also improved their self-confidence and;

84% acquired skills they believed would help them be successful in their future careers

However, studies have suggested that gap year takers may eventually end up earning less than those who go straight into higher education, taking home lower hourly and weekly wages between the ages of 30-38 in comparison. This may be because gap year takers are playing ‘catch up’ with peers who have continued from education into work and are further ahead with their career progression.

Deferral figures from UCAS, saw a 9.4% increase year on year in the number of students from 2019 to 2020, and a further 3% increase from 2020 to 2021. This meant 6,465 more students deferred their university courses in 2021 than in 2019.

Proportional to the total number of students, 2019 saw a 5.6% deferral rate, while 2020 hit 6.26%, and 2021 reached 6.55%. These figures are only representative of those people who held university course offers but declined to attend that year, many more people will have taken gap years without an offer for education through UCAS.

In the U.S. reports stated that there was a 15% decrease between those who intended to enroll pre-pandemic and those who actually did. American analyses of potential college students found that the pandemic encouraged roughly 1 in 10 students to take a gap year, indicating the impact was more severe than that experienced by UK students.

More than half (57%) of students said they faced worsening mental health and wellbeing in their first term of studies beginning September 2022. A further 53% reported that they were overall dissatisfied with the social experiences of university, and almost one in three (29%) said they were overall dissatisfied with their university experience.

All of this contributes to an environment that is not what students expected for their studies. Almost certainly a reason for increased deferrals in 2020 and 2021.

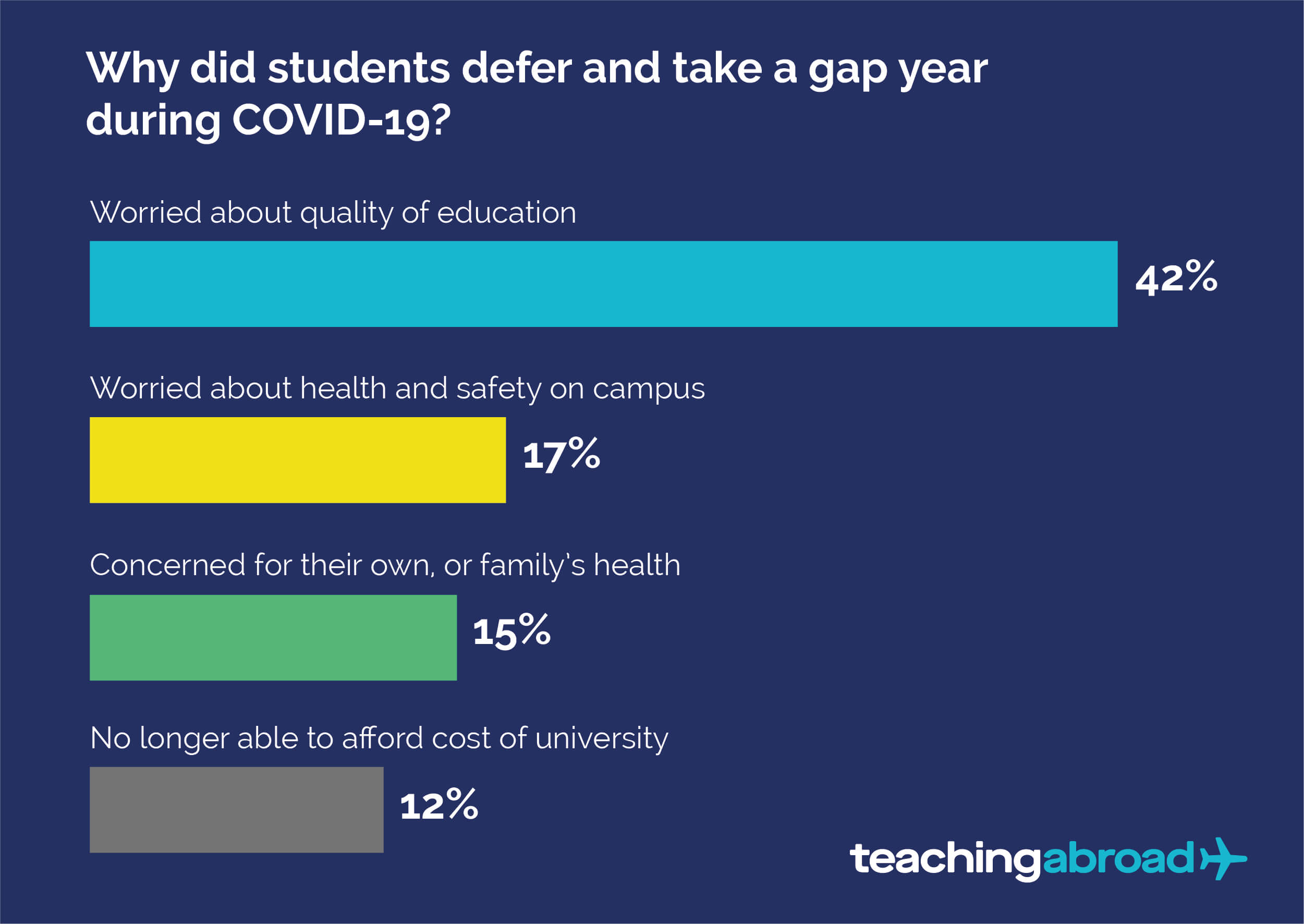

A separate study interviewed students who had recently decided to take a gap year due to the pandemic.

When asked why they were planning on deferring their university course to next year, the most common reason was a concern for the quality of the education they may receive (42%), followed by campus health and safety concerns (17%), personal or family health concerns (15%), and financial worries (12%).

While our analysis intentionally focuses on gap years taken by those under 25, studies in the field have also researched ‘grey gap years’. A grey gap year is a period of time taken by the newly retired, or those over 60, who want to have time away from regular retirement. Typically grey gap years refer exclusively to travel. They were discussed frequently in the media in 2007 and gained traction once again after the pandemic.

Polling from Norwegian Cruise Line in 2022 suggested around 37% of those aged 60+ were looking to do some extended travel similar to a gap year. Taking population estimates from the ONS, that would mean approximately 4.82 million people aged 60-79 could be planning on taking a grey gap year with some long period of travelling.

UK Government, Department for Education, ‘Gap-year takers: uptake, trends and long-term outcomes’ (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gap-year-takers-uptake-trends-and-long-term-outcomes)

UK Government, Department for Education, ‘Youth Cohort Study & Longitudinal Study of Young People in England: The Activities and Experiences of 18 year olds: England 2009’ (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/218911/b01-2010v2.pdf)

Universities UK, ‘Higher education in numbers’ (https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/facts-and-stats/Pages/higher-education-data.aspx)

ABTA, ‘ABTA reveals top gap year destinations’ (https://www.abta.com/news/abta-reveals-top-gap-year-destinations-0)

Budget Your Trip, Various country costs (https://www.budgetyourtrip.com/) Prices correct as of September 2023

The Independent, ‘Does a degree guarantee you a good job?’ (https://www.independent.co.uk/student/career-planning/getting-job/does-a-degree-guarantee-you-a-good-job-795996.html)

UCAS, ‘UNDERGRADUATE SECTOR-LEVEL END OF CYCLE DATA RESOURCES 2021’ (https://www.ucas.com/data-and-analysis/undergraduate-statistics-and-reports/ucas-undergraduate-sector-level-end-cycle-data-resources-2021)

The Sutton Trust, COVID-19 and Social Mobility Impact Brief #2: University Access & Student Finance (https://www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/COVID-19-and-Social-Mobility-Impact-Brief-2.pdf)

Stehlik, T 2008, ‘Mind the gap: researching school-leaver aspirations’, paper presented at the NCVER National Vocational Education and Training Research Conference (No Frills), Launceston, 9–11 July.

Jones’ 2004 report: Jones, A 2004, Review of gap year provision, Research report RR555, Department for Education and Skills, London.

Office for National Statistics, ‘18-24 year old population: All persons: 000s’ (https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/timeseries/jn5q/lms)

Jennifer D. Rubin, PhD., foundry10, ‘A study about COVID-19 and its impact on students' educational plans for the 2020-2021 academic year.’ (https://drive.google.com/file/d/1F1pc3Oy-5-lRGhWx6k02rUMwd6y6n5iu/view)

Office for National Statistics, ‘Coronavirus and higher education students: England, 20 November to 25 November 2020’ (https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/coronavirusandhighereducationstudents/england20novemberto25november2020)

Office for National Statistics, ‘Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland’ (https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland)

Yahoo Life UK, Rise of the 'grey gap year’ (https://uk.style.yahoo.com/rise-grey-gap-year-seniors-travelling-retirement-112000780.html)